Lessons to Take Away Form This Survival Story

Story and Interview

by Paul Bernard, USCG

*Operate with a layered safety strategy.

*Fully plan and prepare for every trip, no matter how quick you think it may be.

*Always file a float plan with a picture of the boat.

*If you boat on or near open water or in remote areas, build a ditch kit and keep it ready at hand, not stowed.

*Check the weather radar and weather forecast.

*Bright colored life jackets matter.

*Have redundant means of communication, remembering that wet cell phones don’t work.

*VHF radios are the preferred means of communication in coastal environments.

*VHF DSC distress (that little red button) is a great lifesaving tool when registered and configured.

*Know your equipment.

*READ THE STORY to learn more about preparedness and about survival and friendship.

Surviving Pontchartrain

Their mothers were pregnant in the same hospital at the same time, and so began the connection between Beau and Jason. Since their birth, the two men have been the best of friends. They have been through some good times and some tough times in their 41 years together. Nothing could prepare them for the hell they would endure in their 18 hour long battle for survival on Lake Pontchartrain on the night of March 31st and April Fools Day morning in 2021.

Jason is an Orthopedic Nurse Practitioner. Beau is a high-level, heavy industry safety professional. Their respective jobs are incredibly stressful and demanding. The two decided that a get-away to Beau’s family camp on the Tangipahoa River on the northwest corner of Lake Pontchartrain (Lake P as it’s known to the locals) was just what they needed to unwind. They built the camp on the river shortly after Beau was born. It has served as an escape ever since.

“My grandfather was in the Coast Guard Auxiliary,” Beau fondly recalls. “He stressed safety to me from a very early age and even had me putting around by myself in a little jon boat with a trolling motor when I was 6 years old.” The safety seeds his grandfather sowed so many years ago would prove crucial during the course of his gut wrenching ordeal.

Jason is a former competitive triathlete. Muscular, lean and disciplined. Jason harkened back to his days as a Boy Scout. “The Boy Scouts helped us grow. During our time as Boy Scouts, we had great leaders who made sure we were mentally and physically strong.” The Boy Scouts were another aspect of life that Jason and Beau shared, and they both mentioned it frequently during our conversations.

Another common denominator that played out in our conversations was their deep concern for the other. While their accounts of the details of their ordeal were, as should be expected, somewhat different, one thing that was a constant was their focus on the well-being of the other. Scarcely a comment would be made without the mention of the other.

The trip was going to be short in both duration and distance, so they didn’t leave a float plan with their families. Because both men simply needed to “unplug” from their demanding professional lives, they left their cell phones at the camp. When they arrived at the mouth of the river, there were no Osprey nests to be seen. The lake was a bit choppy, and while Beau’s deck boat wasn’t ideally suited for choppy open water, it would be fine for a quick, leisurely trip along the shoreline southwest toward Pass Manchac continuing their search for nesting osprey.

Soon after they took up the southwesterly course toward Pass Manchac, the sky began darkening. Then darkening more. Beau realized that a thunderstorm was closing in on them, and they would not be able to make it back to the mouth of the river before it overtook them. The storm didn’t look very large. Beau thought they would be able to head east and go around it. As is often the case with these thunderstorms, they pulse, expanding and contracting in size and intensity. Unfortunately this storm was in an early expanding phase. The further east they navigated, the further east the storm grew. The men put on the life jackets that they kept within arm’s reach.

In an instant the storm overtook them and began unleashing its fury. Lightning crackled through the grim gray sky, the winds gusted with gale force, driving a near horizontal stinging rain, and Lake P began spitting out 4-6 foot walls of water. Lake P is a shallow lake with an average depth of 13 to 15 feet. Shallow bodies of water don’t build smooth swells with substantial distance in between them. They build punishingly steep waves with an average interval of about four seconds.

Those walls of water came crashing across the deck of the boat with unimaginable violence. Beau switched course to try to find his way back to safety. With no GPS or chart plotter, Beau had only a compass to help guide him. Nightfall set in, and the waves the two men could previously see coming would hammer them and the boat by surprise, giving them no time to brace or prepare. Beau made several course adjustments to try to give the mismatched boat the best possible ride and the best chance at remaining afloat. He mentioned trying to get back to the power line that ran over the northwest side of the lake several times as he described his actions and reactions. He knew that the power lines over the lake were a common point of reference, and he rightly assumed that any searchers might use them as a travel corridor. Finding the power line would confirm their location and offer hope.

“Relentless is a good way to describe it.” Beau spoke with lead heavy despair as he revisited that terrifying night. “The waves began systematically dismantling the boat.” First it was the gate on the bow of the boat, then handrails, then seats. Then the steering console began flexing. The steely grip Beau kept on the wheel as Mother Nature tried pry it from his purchase was gradually pulling loose the bolts that held it to the deck.

“Did the lights just flicker,” Beau wondered. Seconds later they flickered again, confirming Beau’s fear. Water had made its way into the bilge and was flooding out the electrical system. The lights flickered several more times before dying completely. They could only hope the engine would continue churning along. It too soon failed, leaving them at the mercy of the stormy seas.

Moments of hope were woven into the night and the following morning. Survivors often speak of the small and seemingly insignificant things that lift their spirits over the course of a protracted survival event. It would be grueling hours before anything that gave even a glimmer of hope would happen again. The warm air had been replaced with chilly air temperatures in the mid 50’s. The air temperature would continue to plummet into the mid 40’s with the passing of the frontal boundary. The lake water temperature was in the mid 50’s.

Beau was wearing a T-shirt and shorts. Jason, a T-Shirt and jeans. They were drenched and had been shivering for several hours and were already feeling the accompanying muscular tension. Hypothermia was beginning its slow, methodical and painful process of draining the life out of the men. The boat began to list heavily to port with a bow up attitude. Jason was on the bow and out of the water, Beau was further aft and partially submerged. While the rain had stopped, the wind continued to howl and every four seconds a cold wave would come crashing over the boat. All they could do was hold on and pray for survival. And pray they did, all through the agonizingly long night.

Periodically throughout the night, Beau would toss floating objects into the water to create a trail for the rescue crews to follow. He knew there would be rescue crews. He was painfully aware that it would be well into the next day before anyone grew concerned and alerted authorities though. Beyond being partially submerged, Beau had another problem. The boat’s fuel tank was leaking. Each wave that slammed into him would deliver a toxic cocktail of lake water and gasoline into his mouth. Both men vomited frequently. Time crawled by, minute by painful minute.

The clouds broke around 10 p.m., providing a moment of hope. The two men could see the lights of New Orleans in the distance and what they figured were the last of the evening’s planes flying into New Orleans International Airport. Beau had hand flares, the kind made with a heavy paper tube, but was unsure of how to set them off. He was also concerned that if he succeeded, it may ignite the gasoline that was floating on the water and had permeated the soft surfaces of the boat. Over time, so much water worked its way into the bilge that the boat leveled out, but it now sat perilously low in the water. The seas eventually subsided slightly, but the winds continued whip the spray off of the waves and onto the two cold and exhausted men. Though with less frequency, waves would still wash over the stricken vessel.

Jason fashioned a wind and spray barrier out of one of the cushions. Hypothermia and dehydration were taking a toll and draining their energy. They didn’t want to fall to sleep, afraid that if they did they may fall unconscious and never awaken. They made a point to check on each other regularly either by tugging on or talking to one another. They were trying to stay positive and conserve energy for the following day when their rescue would be most likely. Jason thought frequently of Beau’s three wonderful children, his Godchildren. He used those thoughts to fuel his will to survive and to keep his best friend alive. As part of Jason’s triathlon training he has taken recovery ice baths. That conditioning was now playing out in his favor. At about 1:00 a.m., Jason grew increasingly concerned for Beau. He tried to find anything on the boat to protect Beau. The boat had a canvas canopy that Jason tried to tear free without success. There was nothing they could do but wait and hope.

It would be another five grueling hours of near constant puking, muscle-burning shivering and, bone-numbing cold before the rising sun cast a hue of purple hope across the eastern sky. The men had drifted some 15 miles from the mouth of the Tangipahoa River. Well to their south, they could see the tractor trailer rigs crossing the Bonne Carre Spillway portion of I-10. Further to the southeast, New Orleans International was coming to life with morning flights. Moments of hope came and moments of hope faded, but the men were determined to survive.

Over the course of the morning they drifted close enough to see Frenier Landing Restaurant several miles to the west. Beau hoped that an early arriving worker may notice the speck on the distant surface of the whitecapped lake. Recreational boaters and commercial crabbers are common on that part of the lake most mornings, but the foul weather was sure to keep them in safe harbor. A helo taking off from the airport, and heading west, offered another moment of hope. That hope too was dashed when they realized its course wouldn’t bring them in contact. They eventually drifted beneath and just beyond the power line on the southwest side of the lake. The powerline too symbolized hope.

A short while later two helos lifted into the sky from the airport. One of them took up a course that would not take it near the boaters, but the other was on a course that would bring it close. They looked for something, anything, to try to wave to capture the attention of the pilots. The first aid kit was orange and the life jacket was purple. It wasn’t much, but they had to try. They waved them both to try to command the attention of the pilots. The men’s prayers were answered when the helo banked and came toward them, then hovered nearby.

Aboard the Bristow Group Incorporated helo, pilots Robert Matthews and Jay Haas were flying on a power line inspection mission. Jay said “the waving purple lifejacket really caught my attention.” The pilots radioed in for help. Recognizing the gravity of the situation, they remained on scene and kept a watchful eye over the survivors. A Coast Guard helo was conducting training in the area and was diverted to the scene. While on training missions, the HH-65 Dolphin helicopters may not carry a full complement of rescue gear and a rescue swimmer. That was the case with this helo, so they relieved the Bristow crew and waited for a fully outfitted rescue helo to arrive from the Coast Guard Air Station in Belle Chasse.

The Coast Guard rescue Helo arrived on scene and lowered rescue swimmer Owen Roberts to evaluate the men and develop the plan for evacuating them. Jason introduced himself to Owen as a medical professional, and gave a rundown of the events of the night and Beau’s medical condition. Owen recalled his initial assessment of Beau. “He was huddled up and couldn’t feel his legs.” The rescue swimmer also noted that Beau experienced difficulty speaking and was suffering a significant degradation in level of consciousness.

A rescue boat from Coast Guard Station New Orleans was just a few minutes away. Beau needed immediate emergency care for his severe hypothermia. Jason was cold and exhausted, but otherwise seemed to be in good and stable condition. Owen and the air crew made the decision to get Beau to the hospital as quickly as possible, and for the rescue boat to take Jason back to New Orleans. Owen later wondered if they had made the best call.

Rhabdomyolysis is a serious syndrome that results from direct or indirect muscle injury. Jason said that triathletes who exert themselves beyond their level of conditioning can suffer rhabdomyolysis. When muscles are subject to extreme stress or injury, they break down and release their toxic contents into the bloodstream. This in turn causes renal failure. The kidneys can’t process the toxic material. Beau was suffering from Rhabdomyolysis. The nearly 18 hours of violent shivering and accompanying muscular rigidity taxed his muscles to the point that they started breaking down. He spent 3 days in the hospital being treated and recovering from Rhabdomyolysis, severe hypothermia, severe dehydration and physical exhaustion. The gasoline induced sores in his mouth made it uncomfortable to eat or drink anything. Had any more time passed before his rescue, he may have suffered grave consequences.

Jason didn’t seek immediate medical attention. He knew Beau was in bad shape when he watched the helo hoist him away, and he wanted to check on him as soon as possible. Jason felt better after changing into some dry clothes, eating and drinking, although he said he felt like he was still on a moving boat several days later. After a few weeks, he still wasn’t feeling quite up to speed. He went to see his doctor. The diagnosis? Rhabdomyolysis. A full two weeks later, and Jason’s kidney function remained impaired. With treatment, he is now back to normal.

I interviewed the survivors a month after their nightmarish experience on Lake P. I talked to Beau for over an hour over the course of several calls. At first I wanted to simply hear his story from his point of view, but then I wanted to chat with Beau, safety professional to safety professional. Like so many of you, I wondered how a person whose profession it is to develop and promote a culture of safety in a hazardous work environment could come so close to losing his life in such a situation.

“So your perception of the risk for the trip you planned to take was that it was an extremely low risk undertaking” I asked Beau. The trip from the camp to the lake is short, and camps line both banks of the river. The boat was well suited for that environment. Indeed it was a low risk venture that required minimal preparedness and risk mitigation.

“Deviations from plans are where things start going wrong,” Beau admitted. He went on to explain that it’s common knowledge in his line of work that three deviations exponentially increase the odds of disaster and decrease the odds that people will reengage the original plan. “I engaged in a series of deviations and mitigation of the risks that the new deviations brought about”, Beau readily acknowledged.

Eventually they strayed too far from their original plan and found themselves in an environment for which they were ill prepared, ill equipped and for which their boat was ill suited. Nobody has to tell these two good gentlemen what they did wrong, they well know.

They made a number of good decisions as well. They donned their life jackets. They used the compass to try to make it back to safety, near shore or near the power lines. They fashioned wind and spray barriers from what they had available. They refused the temptation to make a swim for it. They tossed items in the water to create a trail for rescuers to follow. They used what they had available to signal. They kept each other awake and positive. Perhaps most importantly, they refused to quit. And because of that, they survived Pontchartrain.

A note from the Author Paul Bernard

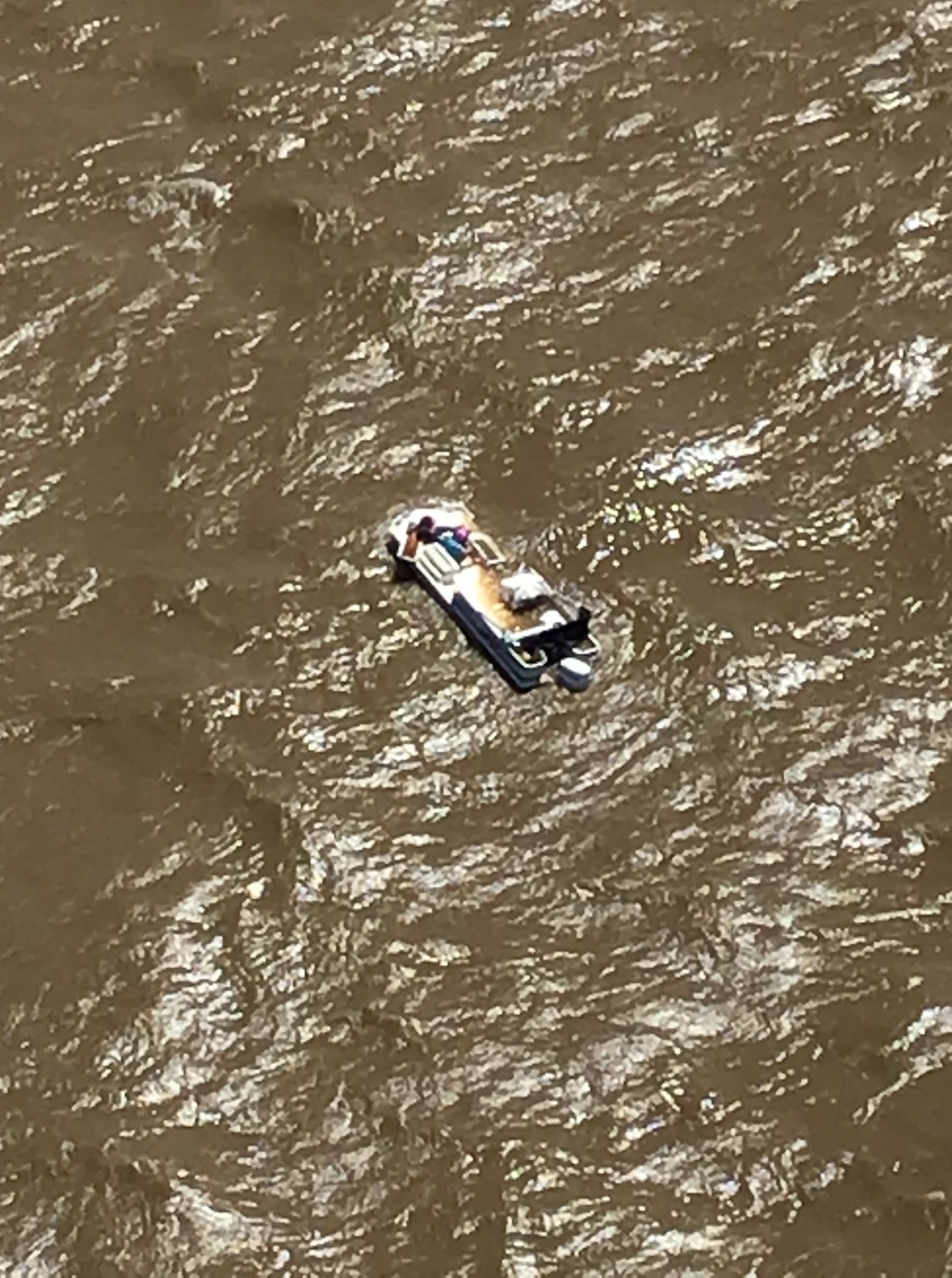

This was a photo from the SAR case I posted yesterday. I wanted to post it again to have this conversation. The photo was taken from the altitude at which we typically fly search patterns.

That’s a 20+ foot boat and it is a speck on the water. Add more whitecaps to the lake, and that boat gets harder to see yet. Imagine how hard it would be to locate a person in the water. That’s part of why staying with the vessel is important, and why brightly colored life jackets and signaling devices attached to, or in the pockets of life jackets are important.

About the Author – Paul Bernard

Paul Barnard has a Facebook Group called U.S. Coast Guard Heartland Safe Boating. This is an official US Coast Guard sponsored group representing the Eighth Coast Guard District. He describes the group administrators as recreational boating safety subject matter experts with the Coast Guard or other boating safety organizations.

Among us are SAR specialists, law enforcement specialists and boating safety specialists. This is a place to discuss all facets of recreational boating safety.

Here you’ll be able to get answers to questions about what you are required to have on your boat, what to expect if the Coast Guard comes aboard, what to do if you need help and much more. We will periodically post boating safety related stories and stories of Coast Guard rescues.