Portrait of an Inessential Government Worker

Glory isn’t part of the deal when you go to work for the federal government.

“I’ve only thought about one problem in my life,” says Art Allen. “Which is how to improve Coast Guard search and rescue.”

Art Allen – Improving Coast Guard Search & Rescue Photographer: Annie Tritt/Bloomberg

October 15, 2019, Updated on October 21, 2019

The following is adapted from a new chapter for the paperback edition of “The Fifth Risk,” which will be published by Norton in November.

I found Art Allen standing on the lawn just outside his front door, a few miles inland from some uninviting Connecticut beach. He was in his mid-60s, and a scientist — but a scientist with a man-of-action feel to him. He wore a Coast Guard Search and Rescue polo and a massive Fenix 3 GPS watch, and he had this snow-white Hemingway beard. Six canoes hung from hooks inside his garage, a scrum of mountain bikes leaned against the wall, and all looked as if they had a lot of miles on them. So did he.

For nearly 40 years, Art Allen had been the lone oceanographer inside the U.S. Coast Guard’s Search and Rescue division. Among other subjects, he had mastered the art of finding things and people lost at sea. At any given moment, all sorts of objects are drifting in the ocean, a surprising number of them Americans. The Coast Guard plucks 10 people a day out of the ocean, on average. Another three die before they’re found. Which is to say that 13 Americans, every day, need to be hauled out of the water or off some crippled sailboat or sea kayak or paddleboard. “I’ve only thought about one problem in my life,” said Art, with an odd little laugh, which sounded half like a chuckle and half like an apology for speaking up. “Which is how to improve Coast Guard search and rescue.”

I’d first learned of Art’s existence back in early 2019, during the 35-day government shutdown. About half the employees of the federal government had been deemed essential for the safety of life and property and been made to work without pay. The other half had been sent home. The line running between the two groups, the essential and the inessential, was oddly drawn. The airport people who make sure that the toiletries in your carry-on can’t be turned into a bomb were required to show up for work. The Federal Bureau of Investigation agents working undercover inside terrorist groups were told to go home. So were the Food and Drug Administration’s food safety inspectors; the people at the Environmental Protection Agency assigned to stop poison from leaking from power plants; and the hundreds of immigration court judges who would decide the fate of thousands of immigrants held in detention facilities.

During the shutdown I’d stumbled upon a very long list of federal workers who had been nominated for an obscure public-service award called the Sammies. Virtually all the people on the list had been laid off without pay and more or less told by their society that their work was not all that important. I wondered what it felt like to be at once up for an award for one’s work, and required by law not to do it. The list was in alphabetical order. At the top was Arthur A. Allen.

Art hadn’t set out in life to save people at sea; he hadn’t actually set out to do anything in particular except to be a scientist. “I think I was always going to be a scientist,” he said. “Science is driven by the love of the subject. I have an aunt who studies the genetics of mushrooms. I don’t know why she finds mushroom genetics beautiful and fascinating, but she does.” What Art had always found beautiful and fascinating was water. He’d grown up on the New York side of Lake Champlain, and even as a little kid his idea of fun was to dig tunnels to drain snow ponds. He went to the University of Massachusetts at Amherst and designed his own major, aquatic science and engineering. From there, he went into a graduate program in physical oceanography at Dalhousie University in Nova Scotia. “Oceanographers come in two flavors,” he said, with the same odd little apology-chuckle. “To find out which one you are, they send you to sea for a couple of weeks. And you either become a theoretical oceanographer — because you throw up a lot. Or you become a field guy. And I was particularly gifted with a strong stomach.”

Book about a Mexican fisherman who survived for 438 days alone on a raft at sea

Photographer: Annie Tritt/Bloomberg

He was also particularly gifted at finding things out. “That was one of my strengths,” he said, but without his odd little laugh. “I could get good data out of the sea.”

The question at the start of Art’s career, back in 1984, was where to apply that strength. He’d seen an ad placed by the Coast Guard for a junior researcher, and while the idea of government work wasn’t as off-putting in the early 1980s as it would become in, say, 2019, Art didn’t really think of himself as a government guy. He certainly didn’t have any sense of being on some mission. “I thought I’d give it six months,” he said.

Just then the Coast Guard was trying to figure out how to improve its ability to spot objects on the ocean surface from its planes and helicopters. It was a little shocking how hard it was to see even a small boat from 1,000 feet; if you flew over and didn’t see it, you might never look there again. To see better, there wasn’t much the Coast Guard wasn’t willing to try. Not long before Art arrived, for instance, it’d attempted to train pigeons, riding in cages attached to Coast Guard aircraft, to respond to any orange object in the ocean by pecking at an alarm. The pigeons seemed to have natural advantages over humans as spotters of objects lost at sea. Their vision was sharper, and they never got bored or distracted. The pigeons didn’t miss a thing, which turned out to be their downfall. “The problem was that there are orange things that aren’t survivors and things not wearing orange that are survivors,” said Art. “The pigeons drove the pilots crazy.”

By the time Art arrived, the pigeons were gone, replaced by questions that Art did his best to answer. For example, the Coast Guard wanted to know the odds of a plane flying at 500 feet over some object actually spotting that object, so Art threw stuff in the water and made people fly over it and try to see it. The Coast Guard wanted him to find better ways to measure ocean currents and winds, so Art built and bought better gadgets to measure them. The Coast Guard needed a device that might better track what was happening to currents at the last known position of some boat or person. Art helped invent a new buoy to do the job.

When a Coast Guard commander looking for a guy lost at sea, and presumed to be floating on a life raft made by the Elliot company, realized that he didn’t really know what an Elliot life raft looked like, or how fast it might travel in relation to the wind compared to life rafts better known to the Coast Guard, he called Art and asked him — and Art called a facility in Essex, Connecticut, that certified life rafts and had them send him a brochure for one. “I’m just looking at it as a pure scientist,” said Art. “They want to know how these objects drift in the ocean, so I figure out how they drift in the ocean.”

In June 2002, off the southern shore of Long Island, a fishing boat was swamped in a storm and threw the four men on it into 60-degree waters. The men had been competing in a shark-fishing tournament when the storm came through. There were a couple of Mustang survival suits on the boat — not enough for all the men. Before they’d capsized, the men had sent a distress signal that was picked up by a Coast Guard station in New Jersey, but the signal was fuzzy and the Coast Guard had no idea where the men were or even, really, if they were in trouble. The real search didn’t get going until that night, when the boat failed to return to port. It lasted four days.

A human can survive in cold water for maybe 36 hours, even inside a Mustang suit, but the Mustang suit company told the men’s families that anyone wearing the suit could last for eight days. The families implored the Coast Guard to keep looking long past the point the Coast Guard thought there was any point in doing so. Three of the men were never found. The body of the fourth was discovered a week later by a fishing boat 30 miles off the New Jersey coast.

When it was over, the people who had failed to find the men called Art with a question: Who’s right, us or the Mustang company? Art looked into the hypothermia models used by the Coast Guard and found they had some problems, apart from the issues raised by the suit. The service made no allowance for the clothing a person might be wearing under the suit, for instance, or his body fat. It assumed the weather was constant throughout the search and that nights in the water were the same as days in the water. “This was another area of Coast Guard ignorance,” said Art. “Survivability.”

Art sought out scientists who had studied hypothermia, and collected what was known on the subject. Even if they’d been wearing the Mustang suits, he concluded, the men almost certainly would have died within two days. These studies suggested to Art that the old Coast Guard models had been, if anything, optimistic about the ability of human beings floating in ocean water to survive. Never mind hypothermia. A person could go only three days without water and 62 hours without sleep before he lost the ability to keep himself alive. But what really struck Art Allen about the whole incident was that “no one really knew.” No one knew how a Mustang suit, or anything else you might be wearing, might affect your ability to survive. Not even the scientists who studied hypothermia.

Art had started his career as a junior researcher, but a decade into it he was the lone oceanographer inside Coast Guard Search and Rescue. And he began to notice something: The people engaged in rescuing Americans at sea were turning to him for answers to questions he’d never been asked. The questions put to him weren’t questions to which he should obviously know the answer. “It occurred to me,” said Art, “that I was getting these questions. And I realize that if I don’t know the answers, no one does.”

People were coming to him because they had nowhere else to go. “Rather than being the wide-eyed scientist in the background, suddenly I’m being asked for my opinions,” said Art. “It was like they thought, There’s this bearded oceanographer guy out there; maybe he knows.” Usually he didn’t know, but he had his talent for creating knowledge.

The biggest thing that no one knew, he decided, was how various objects drifted at sea. The ocean never stopped moving. Every object was pulled and pushed along by currents and winds. And so if you wanted to know where an object might be that had been spotted, say, five hours ago 20 miles due east of Cape Hatteras, you needed to know the winds and the currents off Cape Hatteras in the intervening five hours.

But that knowledge wasn’t enough: You also needed to know exactly what the object was and how it interacted with the forces of nature. Leeway was the technical term for the difference between the movement of an object and the current that pulled it along. “The Coast Guard has always been interested in physical oceanography — oil spills and icebergs,” said Art. “You got stuff that gets into the water and you want to predict where it’s going to go.” Even if they started in the same place, a disabled fishing trawler and a sea kayak might soon be many miles apart.

Art Allen set out to find what was known on the subject. Shockingly little, it turned out. The history of search and rescue at sea is mostly the story of people neither being searched for nor being rescued. For most of human history, lost at sea meant gone for good.

“It really only started during World War II,” said Art. “There was not much looking for people at sea until we started losing pilots in the Pacific.” Scouring the literature, he found that there was really only one good study of leeway. A Coast Guard commander named W.E. Chapline, who had been stationed in Hawaii in the late 1950s, had grown sufficiently weary of not finding people that he had made tests on the few objects on which people lost in the South Pacific tended to float: a surfboard, a sampan, a small fishing boat.

“Estimating the Drift of Distressed Small Craft” was published in 1960, in the Coast Guard Alumni Association Bulletin. It was 2 1/2 pages long and wholly original and, like a lot of things wholly original, had its limitations, which the author hinted at. “It was difficult at times to obtain sufficient volunteers from among the local small boat owners,” he wrote, “due mainly to the discomfort involved while drifting, the relatively small size of the local Coast Guard Auxiliary, and generally small number of boats available in Hawaii.

Otherwise, the short paper was inspiring, at least to Art. It had been done with care, by a man clearly aware that it might one day be the difference between life and death. It contained new insight — like the fact that a lot of boats don’t make their leeway directly downwind. “I’m reading this and I’m saying, ‘Right on, guy!’” recalled Art. There was no reason that Art Allen, Coast Guard oceanographer, could not study every object on which people might drift upon the sea, and reduce to a mathematical equation how each of those objects moved through the water. There was no reason these equations might not be plugged into every search-and-rescue plan. If you knew where some object had been, and when it had been there, you could predict more or less exactly where it was at the moment you needed to find it. If you knew the currents and the winds — which the Coast Guard usually did — all you needed was leeway.

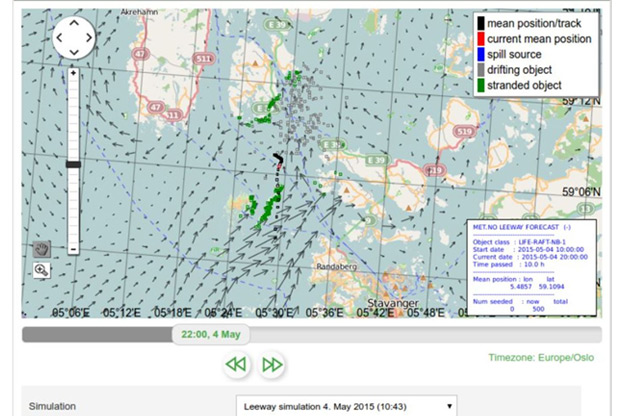

Norwegian operational drift model using Art Allen’s equations. Source: “US Coast Guard Search and Rescue Mission & Operational Oceanography: History, Model Skill, Future Work” by Art Allen via Forum for Operational Oceanography

Without anyone particularly noticing, or caring, Art gathered every object ever studied — the ones in Chapline’s paper, some stuff the Japanese had tested, and objects that had been tossed into the ocean by the Coast Guard and observed. To these, he added 45 or so objects that he’d studied himself, usually after the Coast Guard had failed to find someone said to be adrift upon them. When he was finished, he had a list of 95 different objects: a Tulmar four-person life raft, a 12.5-meter Korean fishing vessel, a Japanese 13-person life raft, a sea kayak, a 100-gallon ice chest, a 65-foot sailboat, a windsurfing board, a Cuban refugee raft with a sail, a Cuban refugee raft without a sail, an airplane evacuation slide raft that Art had persuaded Delta Air Lines to lend him, and so on.

Some items were redundant. Art’s list ultimately reduced itself to 63 classes of objects. For each, Art created equations to describe their drift. The idea was to build the equivalent of those charts you point to when you ask the airline to find your bags: The greater the range of choices, the more likely you will find a bag that resembles your own — and the people who are looking for it can identify it. The thing that was lost might not be exactly like the thing that had been studied, but the closer it was, the more quickly and surely the Coast Guard could design the search for it.

In 1999, Art Allen published everything he knew in a 351-page treatise called “Review of Leeway.” “I only hope that this report is up to the highest standards that were set by W.E. Chapline in 1960,” he wrote in his dedication. Such was his respect for what Chapline had done that Art retyped Chapline’s paper and inserted it into the back of his own. “Review of Leeway” became required reading for anyone going through the National Search and Rescue School. It made Art Allen slightly famous, in his small world. Search and rescue people in other countries began to call and ask him to come and speak to them, or help them with some specific problem.

Even after Art published his treatise, he wasn’t totally sure that it was having its intended effect. The search and rescue people could now, in theory, use Art’s equations in their searches. But they didn’t have a simple computer program that did the work for them, so it was unclear just how the stuff he had learned was being applied. The truth was that, 15 years into his career, Art still didn’t know exactly what happened in the heat of a rescue because he’d never been on the scene during a search. In May 2001, that changed, after a commander in a field office called and asked him if he’d like to see what they did. “That was the first time I got out of the office,” said Art.

The invitation had come from the office in Portsmouth, Virginia. The idea was that Art would spend the first weekend in May with the SAR operator, the person who coordinated the search and rescues in that particular Coast Guard district. The forecast for the weekend was sunny, warm and unthreatening. When Art turned up late in the afternoon, it didn’t really seem like anything would happen. But not long after he sat down with the search and rescue guy, all hell broke loose. There were a bunch of calls for help, one right after another. One boat had run aground. Another boat had caught fire. Yet another boat had capsized and several people had gone overboard in the Chesapeake Bay.

Across the water people were coming to grief. “What had happened was a dry cold front had come through and no one had seen it,” said Art. The search and rescue operator was dispatching helicopters and cutters as fast as he could, and saving one person after another. For help, he had only a crude computer tool and was having to make a lot of calculations by hand. Art was impressed, but after six hours of drama he could see the guy tiring. “And after all of this,” said Art, “someone calls in at the end of the day and says, ‘We have an overdue sailboat.’”

The overdue sailboat’s last known position was a beach it had left that morning. Its intended destination had been the Chesapeake Bay Bridge. It was 20 feet long and equipped with life vests. On board were a man and two women in their 40s, and a 9-year-old girl.

Just how weary the search and rescue guy had become revealed itself when he tried to use a satellite picture to zoom in on the Chesapeake Bay only to realize, after a very long beat, that he was actually staring at the mouth of the Yangtze River in China. Art watched this obviously overwhelmed young man plug crude information into his crude computer tool. He had a fair description of these people’s plans but his program didn’t allow him to input a voyage. Nor could he find good data on the winds over the water — he finally pulled something from an anemometer at a nearby state park. He didn’t even have a good reading of the tides in the bay. On top of all this, he had no drift equations for a swamped skiff, as Art hadn’t studied one. The equations the guy was using came from work on a drifting sailboat done by Chapline in 1960. “I could see he couldn’t adequately plan the search,” said Art. “The tool he’d been given could not help him do what he needed to do.”

Students in immersion suits climb into a raft as part of a safety and survival training program, US Coast Guard Sector Northern New England, Maine

Photographer: Gordon Chibroski/Portland Press Herald

And so the Coast Guard went looking for something without any real idea of where it was. The helicopters and an 87-foot cutter searched through the night, and found nothing. Not until the following morning did the sailboat appear, upside down, a long way from where the Coast Guard had been searching. A fishing boat spotted it. Two adults were in the water beside the boat, alive. A 42-year-old woman and her 9-year-old daughter, both wearing life vests, were taken off the hull. They’d gone hypothermic. A few hours later, at a local hospital, both were pronounced dead.

Art had stayed late into the night and seen all this unfold, in real time. “I watched this happen,” he said, rising from his dining room table. We’d been sitting there talking for maybe five hours before he’d thought to mention the incident. “These two were the same age as my wife and daughter,” said Art — and suddenly he was fighting back tears.

He turned to a stack of papers on a bookshelf. He wasn’t a big keeper of memorabilia. He had some books given to him by a Norwegian search and rescue person grateful for the Norwegian lives he had helped to save. He had a coffee mug with a poem in Mandarin — a tribute to Art, written by the Taiwanese search and rescue people, to thank him for saving Taiwanese lives. The newspaper clipping he now produced was not part of some larger collection of clippings. It was a yellowing edition of the Virginian-Pilot, dated May 7, 2001. A front-page article told the story of Jennifer Curtis Byler, 42, and Sarah Byler, 9. “I was just … ” said Art, haltingly. “This was just a real kick in the teeth for me. For me, it was a real turning point.”

Art’s brother, an electrical engineer, was fond of saying that “a good scientist asks the right question and a good engineer solves the right problem.” Art didn’t put it quite this way, but up until May 5, 2001, he’d been more scientist than engineer. On that day, he saw that the Coast Guard needed him to be both. It wasn’t enough to ask, or even to answer, the questions; he would need to solve the problems. Every day there were more and more data that might be used to find people lost at sea that either wasn’t available or was hard to use.

Both the Navy and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration made observations of winds, currents and water temperature. There were Art’s own studies of leeway, and his equations that described how different objects drifted at sea. What was needed was a computer tool, as simple to use as TurboTax, which instantly grabbed all the relevant data and turned it into a prediction. If Art had been more senior, or more persuasive, he would have created a PowerPoint presentation to sell his superiors on the idea. “I said, ‘I’m not particularly good at making verbal arguments. But I can build something.’”

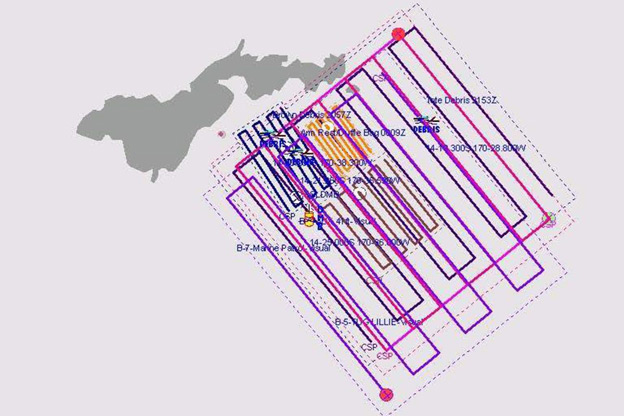

Four years later, the Coast Guard had a prototype. It would soon be the envy of the search and rescue world. SAROPS, it was called: Search and Rescue Optimal Planning System. Art hadn’t built it by himself, of course. No one built anything by himself. But he had taken the lead on most of it and made sure that key information was at the fingertips of search and rescue teams. The SAR operator could now enter a detailed description of the search — two officers, say, peering down from a C-130 flying at 1,000 feet — and SAROPS could calculate the probability of the officers having seen what they were looking for, so they could decide if it made sense to fly over the same patch of ocean again.

The searchers could enter the height, weight and clothing of a person floating in the ocean and, along with the water temperature, figure out how long that person had to live — and so, in the bargain, find out when it was time to call off a search. They could enter the last known location of an object and, because Art had almost certainly studied its leeway, predict how it would move in relation to the winds and the currents.

Often the Coast Guard was unsure exactly what it was looking for. Upright sailboat or an overturned one? A disabled trawler or five fishermen in the water? Now officers could plug multiple objects into their tool and visualize several searches at once. Art’s curious science had yielded information that people could act on.

Search area developed by SAROPS watchstanders looking for a man who went missing in a plane crash off American Samoa in 2014

Source: U.S. Coast Guard

The Coast Guard rolled out its new search tool in early 2007. Art spent two days at each of the service’s nine districts teaching people how to use it — showing them what it was, and what it was not. It was not a simple deterministic device. It did not offer up one distinct answer but a map of probabilities that allowed rescue teams to allocate their search resources in the most likely places. The field people for their part couldn’t quite believe how much more quickly and accurately the new tool allowed them to figure out where in the ocean to look for whatever had gone missing. “The old way took forever to do — it almost took longer to do than the search itself,” said Paul Webb, who ran Coast Guard search and rescue operations in the Alaska district. “You used to launch the planes with a guess. Now you have a search location before the plane is in the air.”

The United States had always been a leader in search and rescue; our country has made more of a priority than any other of saving its citizens at sea. If you were lost at sea there was never much of a question which country you wanted to have looking for you. Now the United States was in a class by itself. Even as Art ran around the country unveiling the new tool, stuff happened that astonished search and rescue people.

For instance, less than an hour past midnight on March 16, 2007, an overweight 35-year-old man who’d had too much to drink tumbled off the balcony of his cabin on a Carnival Cruise ship and into the Atlantic Ocean. But here’s the thing: The man didn’t die. On land, fat will kill you. At sea, it can save your life — and not because it keeps you warm. “Everyone floats,” explained Art, “but the fatter you are the further your mouth is from the water line.”

Someone on the ship, which was 30 miles off the Florida coast, had seen the man go into the dark water and told the captain. The captain had notified the Coast Guard and so the Coast Guard knew roughly where and when the man had splashed down. Still. Spotting a person without a life jacket in the ocean was, as Art put it, “like looking for a soccer ball in Connecticut.”

But now the Coast Guard had a much better idea where to look. The searchers knew the currents and they knew how the man’s body would move in relation to them: his leeway. Interestingly, before Art came along, the assumption was that a person in the water had no leeway. A body was assumed to simply drift with the current. Art had proved that wasn’t true. People didn’t drift exactly with the current and the nature of their drift varied with their circumstances. By the time the man fell off the cruise ship, Art had studied five cases: a person with a life jacket, a person with no life jacket, a person in a scuba suit, a person in a survival suit and a dead person. The people running the rescue plugged in the equations Art had provided for a person with no life jacket. And in March 2007, the following item appeared on a blog under “Cruise and Ferry Passengers and Crew Overboard”:

A 35-year-old man was rescued approximately eight hours after jumping or falling overboard from the ship when it was 30 miles east of Fort Lauderdale. A witness said that the man, who was intoxicated, ran through a window and then fell 60 feet into the ocean — it is not clear whether the window was open at the time. The ship was en route to Nassau and will arrive slightly behind schedule.

They’d found the man 15 miles from his point of entry, floating in the ocean. Had he gone overboard at just about any previous moment in human history, he likely never would have been found. Now the pictures of him flopping down naked but alive on the deck of a Coast Guard cutter were on the front pages of Florida newspapers. With the exception of a great piece in the Baltimore Sun, which described this magical new Coast Guard search tool, the articles mostly told the story of the guy’s miraculous survival. They never even asked the question of exactly how he’d been found.

The answer to that question, at least to the people now using SAROPS, was obvious: Art Allen.

Of course, there was no scientific study to determine the value of Art Allen. “We never take someone and say, ‘Sorry, we’re throwing you back in the ocean and we’re using the old methods to see if we find you,’” said Art. But the response of the people in the field to the new tool was shockingly enthusiastic. “The survivors don’t know what saved them but they owe their lives to Art,” said Geoff Pagels, who runs Coast Guard search and rescue out of Portsmouth. “It’s monumental.”

Despite all the lives saved, Art’s mind found it difficult to move on from the lives that had been lost. The night we were talking in his kitchen, he told me a story: Not long after he had the first working version of SAROPS, he re-created the search for the sailboat that had gone missing in the Chesapeake back in 2001. The new tool automatically pulled in better wind data, as well as the currents and tides, from the day the boat was lost. It knew when the dry cold front swept across the bay and so could estimate when, and where, the boat capsized, and tossed the 9-year-old girl and her mother into the chilly waters. It used Art’s equations for a drifting sailboat — drawing on data that Art had himself harvested. It took only a couple of minutes before up on the screen popped the most likely track the boat had taken. “It took you right to where they’d been,” said Art.

In the fall of 2016, Art told the Coast Guard of his intention to retire in 18 months. When the time came for Art to go in the spring of 2018, the Coast Guard was unprepared. It hadn’t hired his replacement or even given him a junior scientist to train. Like the rest of the federal government, the Coast Guard was aging. At the end of 2018, around the time of the big government shutdown, 18 percent of the civilians employed by the U.S. government became eligible for retirement, and you had to wonder how many Art Allens were walking out the door and not being replaced. What was happening inside, say, the State Department, or the Bureau of Land Management, or the Food and Drug Administration? Art decided to delay his retirement for a year simply because there wasn’t anyone in search and rescue who knew what he knew.

It’s curious how knowledge is at once so hard to create and so easily taken for granted. And in truth it was hard to say exactly what would be lost with Art’s retirement. When the people in the field called Art Allen with a question, it was usually after something had gone wrong. “When things aren’t going right, that’s when I get a call,” said Art. “If things are going right, they don’t need me.” But there were still times that things didn’t go right.

Just before the government shutdown that had pronounced Art inessential, he’d received a call from the Miami district, which had been looking for a missing scuba diver off the Florida coast. Two male scuba divers, one in his 50s, the other in his 20s, had emerged from a dive to find their boat, and its driver, specks in the distance, and strong currents pulling them ever further apart. They were 18 miles from shore. The younger diver decided to swim toward the boat and get help. He never would have made it, but that didn’t matter, as he was rescued by the Coast Guard before he arrived. But in the meantime, the sun had set. The other diver was still out there, alone in the dark, presumably drifting as described by one of Art’s equations.

Art got the call from the search and rescue people that night, after they’d searched the area that SAROPS told them to search and found nothing. A thought occurred to Art that hadn’t occurred to the rescue squad: The guy was trying to swim to shore. Eighteen miles away! The Coast Guard knew, from his fellow diver, that the guy had a scuba suit and orange pool noodles to help keep him afloat. He also had a compass. Art said, Broaden the search, and look closer to shore. “This wasn’t science,” Art said. “It was What would I do if I was in his position?”

The Coast Guard found the diver. “This guy was a survivor,” said Art. “He used his compass. He flipped his mask up and used it to catch rainwater.” On the other hand the guy was still 9 miles from shore, and it was unclear if he was ever going to reach it.

Storage closet where Art Allen kept his gear

Photographer: Annie Tritt/Bloomberg

Many months after the Florida incident, and three months into his retirement, Art took me to see his old office in New London, Connecticut. He’d turned over the little access card that opened the front door, so an old friend had to come down and let us in. Art led me down a long hall with shiny white floors and no sign of human life and into a storage closet, where he’d kept his gear. He seemed sort of pleased, but also a little sad, that it was just as he’d left it: the current meters and anemometers and PVC pipes and mannequins still dressed in life vests. Even the orange pool noodles he’d used when studying the progress of ocean swimmers remained coiled where he’d left them, in the corner.

We then climbed three flights of stairs to his old office, not much bigger than a cubicle and sealed with partition walls. At first glance it looked like what it was: an impersonal government office vacated months earlier by some anonymous public servant, waiting for its next occupant. Keys dangled from file cabinet keyholes; reference books filled the shelves.

At second glance, it was still very much a specific person’s office. The fingers of a ghoulish gray rubber Halloween hand poked out of one of the file cabinets. (“It looks like a hypothermia victim,” said Art, by way of explanation.) Upon inspection the books, too, were singular. One was about a Mexican fisherman who had survived for 438 days alone on a raft at sea. The author had sent it to Art to thank him for verifying that the raft could have indeed drifted as the fisherman described (and everyone else doubted).

I grabbed a pamphlet from a stack on a shelf. “The Leeway of Cuban Refugee Rafts and a Commercial Fishing Vessel,” by Art Allen. “There was an earlier study that said it drifted at 4 percent of the speed of the wind and I came up with 3.98 percent,” said Art, with his odd little laugh. “So what did I add?” Under that pamphlet were other pamphlets — all by Art. At the bottom was his 351-page treatise on the leeway of 95 more objects. On the cover was a note. “To my successor:” Art had scrawled in thick black ink. “You will find this report will provide a good background on the search objects in SARS. All the best, my friend. Art Allen.”

“It’s really kind of sad, isn’t it?” he said.

Art Allen had done what he’d done without asking for much for himself. Back in 1984, as a GS-11, he’d been paid less than $30,000 a year. After 35 years, he’d risen to a GS-14, and he’d been paid a bit more than $100,000. He hadn’t even expected the attention of others, outside his small circle of search and rescue people. It was nice that the Taiwanese coast guard wrote poems about him. But that sort of thing rarely happened here, in the United States. And he didn’t expect it to happen: Glory wasn’t part of the deal when you went to work for the federal government. Stability, on the other hand, was. He’d never expected to be chased from his job.

There’d been a moment, a few years earlier, that captured the spirit of Art Allen’s relationship to the society he’d tried to save. He’d flown to Long Beach, California, to help the Coast Guard search and rescue people there upgrade their search and rescue tool. Purely by accident, he’d arrived on the day a ceremony was being held to honor the heroes of a recent rescue. A few months earlier, a Los Angeles man had fallen off the back of his brother’s fishing boat, without anyone noticing what had happened. He’d floated in the Pacific for seven hours. The Coast Guard had plucked him from the water in the middle of the night.

On the day of Art Allen’s visit, the guy who’d been rescued had returned to the Coast Guard station to thank his rescuers. His visit had attracted the interest of local media. A bunch of TV cameras were there to witness the moment as the guy broke down and confessed that the experience of floating for hours in the darkness, and then by some miracle being saved, had left him a changed man. He’d quit smoking and lost 30 pounds and tried to help other people in distress.

Art stood off to one side, respectfully, and watched as the television cameras turned their attention from the man to the Coast Guard patrol that had saved him. “Against all odds, the crew detected yelling and a faint whistle in the darkness,” someone said into a microphone as the patrollers stepped forward, in turn, to receive their medals. Just then an older Coast Guard guy who had worked with Art Allen for many years leaned over and whispered to him, but to him alone: “Nice job.”

Michael Lewis is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist. He is a contributing editor at Vanity Fair, and his books include “Flash Boys: A Wall Street Revolt,” “Moneyball: The Art of Winning an Unfair Game” and “Liar’s Poker.”This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Bloomberg Opinion: Politics & Policy

By Michael Lewis, mlewis1@bloomberg.net

October 15, 2019, 5:00 AM EDT Updated on October 21, 2019, 2:59 PM EDTTo contact the editor responsible for this story:

David Shipley at davidshipley@bloomberg.net